Arthur Smith's Dueling Banjos received its name because the piece is a musical duel between a banjo and a guitar player. The evidence of this duel lies in the polyphonic texture of the song. This polyphonic texture is developed through the use of imitation and sequences. At measure 7 and continuing through the third beat of measure 14, the guitar (top staff bracket) and banjo (bottom staff bracket) exchange chords. The guitar begins at measure 7 with a set of G major triads in first inversion that start the I-IV-I chord progression using both the first and second inversions of the chords. The banjo imitates the guitar with another I-IV-I progression (Figure 1).

The two instruments imitate each other which provides a

solid foundation to the polyphonic textures of the melodic lines. The use of

the same chords in this system further emphasizes the dueling aspect of the

song as it paints the scene of one instrumentalist trying to out-play the other.

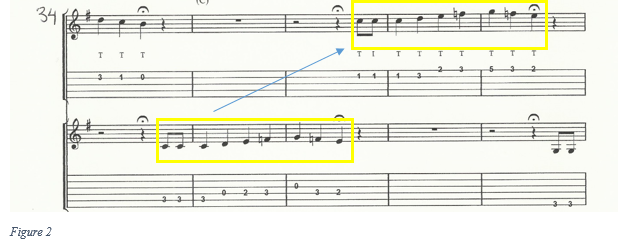

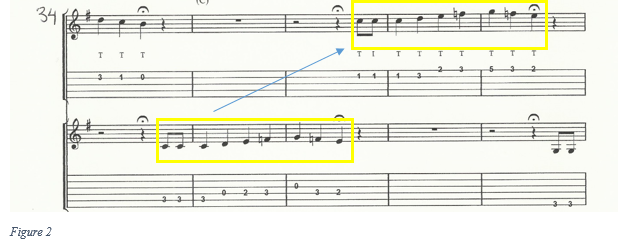

From beat 4 of measure 34 to beat 3 of measure 38, a motif is sequenced and is brought out through the independent melodic lines of both instruments. This is an example of sequencing because the musical motif is repeated with a different starting pitch while maintaining the exact interval relationships of the original motif.

The dueling theme of polyphony is

brought to life as the music picks up speed at measure 49. It is at this point

that the instruments are taking the duel to the next level. The guitar and

banjo play the same chord progressions as the two polyphonic line partake in

imitation. (Figure 3).

While Johann Sebastian Bach’s

Invention No. 8 is not nearly as long as Smith’s Dueling Banjos, it is just as

complicated, if not more so. Both the treble clef and bass clef notations can

be played separately, while still maintaining a melody. This is achieved

through imitation and sequencing which keeps characteristics of the melodic

line separate from one another while still enabling them to be played together.

The invention has “all the effectiveness of a canon without the stiffness

almost inseparable from an extended strict adherence to that form” (How to

Study the Two-Voices Inventions of Bach).

From the first two measures of

Invention No. 8, a polyphonic texture can be identified through the use of

imitation. At measure 1, the treble clef begins by playing a steady eighth note

rhythm that the left hand begins to play at measure 2. From measures 1-12, the

bass clef part is one measure behind the treble clef (Figure 4).

In the treble clef at measure 4 is where the

first signs of sequencing come in. The treble clef plays three groupings of a

sixteenth-note motif that is shifted down a major third in measure 5. The same

motif in measure 5 is then shifted down a minor third in measure 6. The

measures are homorhythmic and keep the same interval relationships which can be

seen in measures 5 and 6. This use of sequencing is also notated in the bass

clef as the sixteenth-note motif begins at measure 5 beginning one octave lower

than the original sequence in measure 4 in the treble clef. The sixteenth-note

motif is shifted down a major third in the bass clef in measure 6 followed by

shifting an additional minor third down in measure 7. The treble clef notation

at measure 7 uses sequencing as yet another sixteenth-note section is shifted

down throughout the measure (Figure 5).

In measure 19 of the Invention, the

treble clef uses a sequence of the diminished seventh interval pattern

previously found in the bass clef at measure 15. Measure 20 in the bass clef is

a sequence of measure 19 as the pattern is shifted down a second (Figure 6).

No comments:

Post a Comment